A Science-Based Vaccination Schedule For Your Dog And Cat

Ron Hines DVM PhD

Why do some vaccines last a lifetime while other vaccines don’t?

I wrote much of this article before the COVID-19 epidemic began. It’s a different world now, and many of you are wondering why your physician is likely to recommend that you have a Covid vaccine booster shot every year, while your dog doesn’t require a canine distemper or parvovirus, booster every year. Your cat won’t require a panleukopenia, rhinotracheitis, or feline leukemia booster every year either. The reason is the mutation factor. Some viruses, like COVID-19 and influenza that affect us, replicate and mutate rapidly to avoid the immunity present from prior vaccinations. While other viruses, like Tetanus, Polio, Smallpox, Hepatitis A & B and Measles are quite different. They are much more stable in their genetic composition and unlikely to mutate enough to escape the immunity of prior vaccinations you received. That is why a shot-series against those stable viruses in childhood lasts us most, or all of our lifetime. The same goes for the vaccines we veterinarians give your pets: Canine Distemper, Adenovirus, Parvovirus, Panleukopenia virus, calicivirus and feline leukemia are all stable viruses too. Measuring your dog or cat’s antibody levels against them doesn’t give you the whole picture of how well your pet is protected because besides antibodies, vaccines give long-lasting immunity by training your pet’s memory B and T cells.

*************************

My postman arrived yesterday with one of my favorite veterinary magazines. Among the various announcements, there was one touting the superiority of Boehringer Ingelheim’s new 0.5 ml ULTRA® line of dog and cat vaccines. No problem there – they might sting small dogs less and be less painful when giving shots in the lower legs or tail of cats. There’s not much space between your cat’s skin and the muscles of its legs or tail to deposit vaccines (those are the recommended locations now). (read here)

But what the announcement also made clear is that we are not making much progress in our efforts to drive a stake through the hearts of those who continue to seek to vaccinate your dog or cat yearly – or too frequently throughout their lives. Scientifically-based vaccinations schedules for your pet are still uncommon. Clicking on the image to see their ad. It shows you that the Company still suggests yearly vaccinations as an acceptable option – and never less frequently than 3 years apart. There is absolutely no need for that! (read here & here)

Is The New 0.5 ml Vaccine Dose A Safer Dose?

Like I said, a smaller volume dose might be of some benefit to smaller dogs and to cats. However, the Company’s marketing campaign is disturbing. It is an example of what happens when the sales team preempts the scientific team and starts making medical decisions in an effort to increase sales. Their marketing campaign offers a quick fix to growing public awareness of the dangers of over-vaccination. Many pet owners like you now know that over-vaccination of pets offers no health benefits and poses many potentially negative health consequences. But most dog and cat owners are not quite sure why that is. Offering low-volume/high concentrate vaccines allows a veterinarian willing to do so to say to you “don’t worry, we have cut the volume in half so over your pet’s lifetime it will get much less (think a safer option) vaccine”. Sort of like offering to sell me a scale that reads 50% less to help me solve my overweight problem or smoking “all organic” cigarettes.

In their non-public survey, Boehringer Ingelheim reported that dog and cat owners believe that “reduced injection volume over the lifetime of their cat is an important feature in a vaccine”. If that is true, it’s because many pet owners still think that vaccine volume (amount) is what is causing problems. It isn’t. It’s what is in the product, not its volume, that is important. Designed “for a more comfortable vaccine experience” and pet owner” peace of mind” is not a recipe for a more healthful vaccine experience. And the “significantly less vaccine volume over the cat’s lifetime” has nothing to do with the dangers of frequent, unnecessary jabs.

They say, “just trust us”, we have the “data on file” (only you and your veterinarian don’t have permission to see it). There is no proof that a 0.5 ml, more concentrated product, is any less inflammatory or has any less negative effects on your pet’s immune system than a 1.0 ml product containing the same amount of active ingredients. If there was some sort of health advantage, they would certainly have mentioned it. Veterinary pharmaceutical companies are never shy abut sharing data that is positive to their wares.

Vaccine induced fibrosarcoma tumors in cats, related to the inflammation vaccine ingredients cause, are the most visible example. It is the only one we can accurately quantify at this time. No one has a shred of evidence that the volume of the product that was injected has anything to do with later tumor formation. Even microchips, devices with 1/10th the volume of a 0.5 ml vaccination, occasionally induce fibrosarcomas in cats. (read here & here) Even a piece of cotton accidentally left behind during spay surgery can do the same. (read here)

The incidence of those tumors in American house cats is estimated to be about 1-2/10,000 client cats. (read here) When I still offered online consultations, many of my clients resided in the UK. In England, where pressure to over-vaccinate dogs and cats had not become intense, the incidence was found to be 1/50,000 cats in a 260 unbiased veterinary hospital sample. If the fibrosarcoma cancer rate only went up to US levels in “problem” hospitals. (read here) You can guess why that was.

Volume is probably irrelevant to neoplasia (cancer) or vaccine reactions. A reduced volume, more concentrated product, might be better or worse, but no one can tell you that today. The surface antigens (polysaccharides and proteins) that normally coat bacteria and virus or whole weakened virus (MLV vaccines) are the important things all vaccines contain. You cannot remove them through ultra-filtration or reduce their amount without decreasing the effectiveness of the vaccine. In some vaccines, such as those against leptospirosis, they are probably the same elements that have the potential to cause undesired reaction as well. (read here)

There is ongoing research on the benefits of giving smaller pets smaller doses of regular 1 ml standard vaccines. But that is something entirely different and those results have not yet been published.

What Vaccines Need Boosters Vaccinations Frequently During My Pet’s Lifetime?

Only the ones that produce poor immunity – even after a natural infection – need frequent boosters. They are against the diseases your pet could potentially catch again and again. Those are things like kennel cough/bordetella, Lyme disease and leptospirosis – if you feel the risk of your pet catching those are sufficient to pose a threat. Kennel cough is a minor disease in most pets; Lyme disease is not. Herpes1 virus (Rhinotracheitis, Cat flu) of cats is another virus that produces poor or incomplete immunity. But most cats are exposed to that organism as a kitten and never completely clear the virus from their system, so re-vaccinating them against it is of no value. Feline leukemia is a disease of young cats, after an initial series in youth and a booster at one year; there is no need to ever vaccinate them again.

You might say: “well, I need a flu shot every year – don’t I ?” You get a yearly flu shot not because you need a booster. You get them because the influenza virus mutates from year to year. Every year, the vaccine is different because every year there is a new strain of virus. But pet diseases like feline distemper (panleukopenia) canine distemper, canine adenoviruses, feline leukemia, parvovirus of dogs and calicivirus have been quite stable over the years and the immunity the vaccines against them impart to your dog or cat is very long-lasting. New subspecies (serovars) do pop up occasionally, but until now, at least, vaccines designed with the older strains still protect. But if they didn’t, no number of booster shots with the strains your pet got before would be of any benefit.

Rabies is a dreaded disease, a potential public health concern and a regulatory issue. We know rabies vaccines similar to the ones your pet receives protect for 10 years or more. (read here & here) Out of fear and official public health concern, the vaccines are only certified for 3 years and, with science overlooked, many states insist they be given yearly.

The NIH

The National Center for Biotechnology Information is a branch of my former employer, the National Institutes Of Health. If you visit the NIH website, you have access to 30+ million scientific articles published since 1966 and many before that on PubMed. If you type in vaccination failure + dog or + cat. You will bring up zero articles describing a dog or cat whose vaccination failed to protect it from disease when its initial vaccine series was given properly. All you will find is a rare article that reports a pet vaccine technical failure when the animal was: 1) Vaccinated at too young an age. 2) Already infected before it was vaccinated. 3) Became infected within a a day or two after the vaccine was given but before it had time to produce protective antibodies, 4) Wast was seriously sick or nutritionally deprived at the time of its vaccination or 5) was suspected to have a genetic defect in its immune system. In the 5th case, it was usually the modified live virus in the vaccine itself that grew and caused illness. (read here & here) In others the most important 14-16 week booster vaccination was missed. (read here, here & here) That mirrors my personal experience. I have never seen a true case of vaccine failure or met another veterinarian who has.

Veterinarians tend to quote one of three vaccination “guidelines” when justifying frequent adult vaccinations for your dog and cat. If you have a cat, they quote the AAFP Guidelines

If vaccine manufacturers and these “panels” had the slightest evidence of the need for yearly (or every 3-years) vaccinations after a puppy series and a booster one year later, don’t you think they would present that evidence by now? If they had evidence (other than the fallacy of titer decline) that they needed lifetime boosters every three years, don’t you think they would present that evidence as well? These folks have had 70 years to do so. Until they do, their recommendations and those of various “advisory panels” are pure conjecture. I believe that it is wiser to follow the lead of human physicians who have accumulated vastly more data on the persistence of immunity subsequent to vaccination and who are somewhat freer from the influences of those who might profit financially from those injections. Pediatricians actually lose money every time you vaccinate your child. (read here)

What Can I Learn From Human Medical Research Regarding My Dog And Cat’s Need For Frequent Adult Vaccination Boosters?

It is just as unrealistic to expect veterinary vaccine companies to encourage you or your veterinarian to use less of their products, as it is to expect Coca-Cola to encourage you to drink less of their sugary drinks. That is a decision that you will have to have the courage to decide for yourself. Veterinary vaccine manufacturers and those indebted to them are never going to suggest it. The veterinarian trade association, the AVMA, is not going to either. Money and power fuel the AVMA bureaucracy, not your pet’s long-term welfare.

But you can gain confidence in your decisions by examining what human vaccine research has discovered regarding how long similar vaccines protect people. We differ from our pets in many ways. But you and your dog and cat share the same core set of DNA instructions (genes) that mold the mammalian immune system. (read here & here) The most important genes that guide you and your pet’s response to vaccines are the MHC group.That important gene group has moved between chromosomes over eons, but they are present (conserved) in all mammals. see here:

Here Are Some Examples Of How Long Immunity To Some Stable Viruses Lasts. Veterinary Vaccine Manufacturers Are Reluctant To Run Similar Studies, For Obvious Reasons

Tetanus

After your initial 3-shot series, a booster is only suggested every 10 years.

Polio

After an initial pediatric 3-shot series and a booster at 4–6 years. No further boosters are suggested.

Hepatitis B

After the initial 3-shot vaccine series, you are protected for life. Even humans who no longer have detectable antibodies in their blood remain protected.

Pneumococcus

When you hit 65, the CDC suggests an anti-pneumococcal vaccine booster after your original childhood series. An aging immune system sometimes needs a reminder.

Yellow Fever

Thirty to 35 years after a single vaccination, recipients of the vaccine are still protected.

Rubella

A single vaccine dose protects for over 10 years.

Diphtheria

After your initial childhood series, a booster is suggested every 10 years. But that is only because it only comes in combination with tetanus and the CDC recommends a tetanus booster every 10 years.

What Can We Learn From Human Medical Research And Animal Studies Regarding The Dangers Of Over-vaccination?

We and our pets all need vaccinations. But we need them at the right time, in the right amount and only when the risks of the diseases for which they are given are greater than the risk of giving the vaccine. When your pet (or you) have a specific genetic immune system makeup, the risk of a given vaccines may be greater than for an individual having a different genetic makeup. Those risks factors are still very poorly understood and probably very complex. But because of the work of the Broad Institute, we will soon understand why some of our pets are more at risk for these reactions than others.

Perhaps some day there will be tests that your veterinarian can run to tell you in advance how great those risks may be in your specific dog or cat before suggesting vaccines or vaccine boosters. But until that time comes, giving vaccines to dogs and cats that we know are unnecessary is unconscionable. Besides being a waste of time, effort and expense, those vaccines have been documented to occasionally produce (or perhaps exacerbate [make worse]) a large number of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases in humans and animals. (read here) They do so by stimulating the production of antibodies that attack the body itself (autoantibodies). Some blame this on adjuvants (enhancers), added to the vaccines to improve their effectiveness. Others on characteristics of the immunizing ingredients themselves. Others on “molecular mimicry” – the fact that an injected molecule is so closely related to a normal molecule in the pet’s body that the antibody produced attacks both. Others to the formation of promiscuous antibodies that attack more than one thing.

Some believe that pet vaccines that contain no adjuvants are less likely to cause these problems. Others believe that live organism attenuated (weakened) vaccines (MLV) may be safer than killed vaccines. Both sound reasonable; but neither has been proven.

Several studies suggest that over-vaccination of cats can result in eventual kidney disease. (read here & here)

Does My Pet Need A Vaccine Booster Whenever Its Antibody Titer Levels Drops?

Your dog or cat is probably capable of making a trillion different antibodies during its lifetime – we know we humans can. (read here) But if high levels of unneeded antibodies to everything your pet encounters in life were maintained indefinitely, these antibodies would eventually build up to unhealthy levels. That is called hypergammaglobulinemia. If something like that occurs (as it occasionally does for different reasons) it is also called a polyclonal gammopathy (too many antibodies). Such a situation is deleterious (bad for) to the health of humans and pets. (read here)

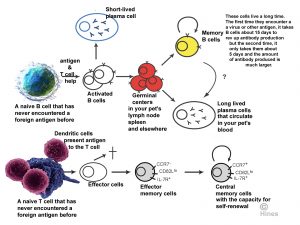

The diagram above shows how Nature took that into account. Instead of having to maintain high antibody levels against too many things, Nature relies on immunological memory. It is normal for your dog or cat’s antibody levels (titer) against the diseases we veterinarians vaccinate against to drop slowly over time. It happens in you and me as well. But immunity persists long after those antibodies are no longer detectable. That is because of that phenomenon called immunological memory. When certain cells in your pet’s immune system encounter an invader or a vaccine for the first time, some, released from your pet’s bone marrow, produce antibody. But others become memory B cells and others, released by the thymus gland, become memory T cells. Memory T cells are known to live longer than 20 years; memory B cells for 60+ years after a smallpox vaccination. When a human or an animal is again exposed to whatever that long-ago vaccine injection or infectious agent was, these memory cells rapidly stimulate the production of new protective antibodies. This is called an anamnestic response = (quick recall – “I remember seeing this before and I know what to do”). So, the fact that your pet no longer has detectable antibodies to say, canine distemper or parvo, or to feline leukemia or panleukopenia does not mean it is no longer immune to those diseases. Each pet acquires a unique memory profile based on the infections and vaccines it encountered throughout its life.

We love our pets, and we like reassurance that we are making the best decisions for them. If you have lingering fears that your pet might not be protected, you can have a virus neutralization blood test performed on it. (read here) If those types of antibodies are still present, a booster vaccination is unnecessary. But if they lack those antibodies, your pet may still be well protected through its immunological memory. We just do not have a simple test that can measure the presence of immunological memory in our pets yet (other than finding an anamnestic response after a vaccination booster). Only one study examined this phenomenon recently. You can read it here.

How Can I Be Certain That The Vaccines My Veterinarian Gives Protect Without Giving Them In Excess?

I see no benefit in giving vaccinations of any sort to puppies and kittens less than 12 weeks old unless they are kept in very high-risk situations such as shelters or unsanitary pet stores selling puppy-mill animals. It gives a false sense of security. Too many of those early shots fail to protect the pet because of the amount of their mother’s residual antibodies that still circulate in their system (Some have suggested that giving these premature shots might actually decrease the youngster’s ability to fight infections. (read here) Animals that young only need a general health exam, parasite control (worming) isolation from sick animals and your TLC. But there are some rules that you must abide by. Virus do not drive to your house and knock at your front door. You bring them home through your actions.

Never take these pets that are possibly still unprotected to doggy parks, groomers, kennels or dog and cat shows. Don’t show them off to your neighbors. Don’t let your kids do that either. Do not let them mingle with other pets in veterinary hospital waiting rooms. Do not place them in environments that recently had sick animals. Do not get in line with your pets at mobile clinics. Cary your young pet in your arms when you leave your home. Do not allow your pet access through fences to the neighbor’s dogs or cats – particularly if they are not responsible pet owners. If you visit animal shelters, take a bath and change your cloths when you get home. I volunteer at my local shelter. For all the blessed things these facilities do, they still face diseases day in and day out. Use other common-sense strategies to prevent disease exposure in your young animals until a week after their last puppy/kitten shot.

How Often Do You Suggest These Vaccination For My Pet?

1) At 12 weeks of age, have a low-volume (ie low traffic) animal hospital with a vet you trust, or a house call vet come to your home and give the pet the first of its 3 injections against the core diseases I mentioned earlier. I never include lepto in these initial vaccinations, just do not expose your dog to situations where the leptospirosis bacteria are likely to be present. Remember that veterinary waiting rooms, like ER waiting rooms, can be great places to catch the flu as well as to recover from it – don’t introduce your new pet to the rest of the animal crowd.

A perfectly valid alternative to this early vaccination is to isolate your pet from the common sources of disease: no contact with other non-family dogs or cats, no doggy parks, no boarding, no groomers, no doggy daycare, no wandering cats, no tracking virus home from the homes of friends or animal shelters, no show-and-tell, no new dogs or cats brought home, no animal hospital waiting rooms, no fostering, no shared utensils, etc. Shots take time to work and exposed pets can go many days before signs of illness become apparent.

Puppies in particular need early socialization to protect them from later fears and phobias. (read here) That critical window for healthy socialization of a puppy is 8–16 weeks of age. Rather than taking your dog to places where many unknown dogs congregate before your puppy’s vaccines are fully protective, consider inviting friends to come over to play with your puppy and bring their well-adjusted adult vaccinated dogs along.

2) At 14 – 16 weeks of age, have your pet receive a booster vaccination with the same vaccine.

4) One year from then, have your pet receive a booster vaccination for its core diseases. In dogs and cats with normal immune systems, there is no need to repeat them after that for at least 7 years. Remember that no studies prove how long veterinary vaccines protect. Mine is just an educated guess – more cautious than one of the most frequency given human vaccines, the tetanus/diphtheria toxoid vaccine for which a booster is recommended every 10 years. (read here) But remember, just like us, there will always be a few outliers – dogs and cats with defective immune systems – that react badly to vaccines. I would not personally repeat a specific vaccination in a vaccinated adult dog or cat that had such a reaction or was allergy prone. (read here) Unmentioned in that reference is that those vaccine reactions are notoriously under-reported. read why here:

5) If you obtain a healthy adult (5 month+) pet with an unknown vaccination history, I believe that a single initial vaccination is sufficient (2017 AAHA guidelines agree, even “high-risk area” dogs need only one).

6) A single booster vaccination in your pet’s elder years might be wise as well. (read here)

If you feel a leptospirosis vaccination is appropriate for your dog, have your veterinarian begin a two-shot series a week after finishing the core vaccinations and boost the lepto 4 weeks later. Do not let others make that decision for you. The same goes for all non-core vaccinations such as Lyme disease and canine influenza. I do not recommend combination vaccines that have the lepto organisms in addition to core diseases (that is, none that have___ ___ ___ +Lepto or +L). (read here) If you decide that the benefits of leptospirosis vaccinations are less than their risk to your dog, it will be up to you to protect your pet from encountering that bacteria. That means not turning your dog off-leash at iffy doggy parks or recreational areas where many dogs urinate and preventing its exposure to raccoon and rat urine and sewerage.

Remember that vaccines do not give instantaneous protection. Remember that new pets, particularly those obtained from shelters or backyard breeders can be incubating these core diseases when you get them. In those cases, it wasn’t the vaccine that failed – it was the provider of the pet who failed. Also remember that unhealthy, stressed or heavily parasitized pets of any age have unhealthy weakened immune systems as well. It is wise to give them an additional booster after they have regained their health.

That is how I managed vaccines for my cat, Oreo, and how I manage them now for my Labrador retriever, Maxx.

If I Follow Your Suggestion, Will 100% of Dogs and Cats Be Immune To These Diseases?

There are no 100%s in veterinary medicine. It just doesn’t work that way because the biology of life is too complex. I do not believe that any vaccine schedule is going to protect 100% of any animal – if the group it is given to is large enough. There will always be the rare exception: The pet with a defective immune system. Some form of error in the vaccine manufacturing process. A sudden mutation of a disease organism. An anaphylactic or autoimmune reaction, etc. We just cannot account for all the unforeseeable things life brings to us and our pets. But I believe that the dangers of over-vaccination are far greater than the dangers of limiting those shots to what is most often required. That is particularly true in dogs and cats whose individual genetics make them susceptible to autoimmune and post-injection inflammatory diseases. Many AKC and CFA breeders breed for cuteness and what sells or, if you are lucky, specialized abilities, but rarely for longevity and general health. Dog vaccines have been around since the 1940s and livestock vaccines since 1879 and there is still no science that I can furnish you with to make your decisions on an “ideal” pet vaccination frequency.

The reason conscientious veterinarians give three kitten or puppy shots is because the window for successful vaccination protection is not exactly the same in any two litters. But with three shots, and then again at the end of that year, veterinarians are most likely to have one or two shots that are timed perfectly. Newer vaccines seem better at overcoming residual interference from the mother’s antibodies than the older ones did.

At normal room temperature, no more than one hour should elapse between the time the two vials are mixed and the time that mixture is injected.

Are There Special Pets That Might Need More Frequent Booster Vaccinations?

Kind-hearted people who care for strays and run animal shelters face their own predicaments. The animals come to them stressed. Many are in the midst of infectious disease. Their vaccination history is unknown – most have received none. The staff is often overwhelmed with the number of animals they must care for. The animals are housed close together. Most are not at the facility long enough for a proper vaccine series. Volunteer staff come and go. Money to make improvements or for complex health care is scarce. So optimum shelter medicine is quite different from optimal veterinary medicine for a well cared for pet like yours. Suggesting the same vaccine protocol and vaccine schedule for shelters as for pet owners is quite silly. I did not write this article for folks in shelter situations.

Your dog or cat’s ability to respond to the vaccines your veterinarian administers or diseases it might encounter depends on it having a strong, underlying immune system. Many chronic diseases, lower your pet’s ability to fight infections of all kinds or to respond to vaccinations. So dogs and cats whose immune systems are compromised by things like cancer, autoimmune disease, diabetes, heart and lung disease or kidney disease might have less immunity to the diseases they were vaccinated against in their youth. If a booster vaccination in those pets might be helpful is unknown. If given, I would suggest they be all-killed (no live modified organisms) product. Buy I, myself, would be reluctant to give any vaccines to such animals.

Any medication that affects your pet’s immune system has the potential to alter its response to vaccines. Corticosteroid drugs like prednisone, drugs used to fight cancer or chronic allergies (read here) And possibly nibs similar to Apoquel®/oclacitinib (a “cousin” of Xeljanz®/tofacitinib). All-killed or subunit (e.g. canary pox vectored) products might be safer to use in pets in these situations and post-vaccination virus neutralization titers might be desirable. The worry is not just that ordinary vaccines in these animals might not be as effective. It is also that in those pets, the weakened live virus vaccine (MLV) might still be capable of causing the disease it was given to prevent. The same applies to the occasional dog or cat that is born with an abnormal immune system. (read here)

Advancing years also lowers disease resistance. A cocker spaniel of 14 years or a cat of the same age is about equal in age to a human of 70-73 (a large dog like a Rottweiler would reach that equivalent age at 10) Perhaps a booster vaccination at that age might be appropriate – even though vaccines in the elderly tend to be less effective. Veterinarians really do not know. Besides, it is extremely rare for veterinarians to see infectious diseases in elderly dogs and cats – recently vaccinated or not. When and if those oldsters are re-vaccinated, an all-killed or subunit (e.g. canary pox vectored) products might again be safer to use in them. That should avoid fears of things like “vaccinal distemper” or old dog encephalitis. (read here)

Who Is Responsible For This Mess? Perhaps These folks are too:

I am not in the least bit anti-vaccination. I’ve always felt that I do my clients and their pets an important service when I administer vaccines – when the pets actually need them. But when I have little faith that a vaccine is effective or required or if I feel the risk of a non-core disease is very low – I tell that to my clients as well. I tell them that it is up to them, not some vaccine company-sponsored group, to make those decisions.

It is our changing veterinary landscape that is causing the problem. Today’s veterinarians operate in an ultra-competitive environment. Your independent small veterinary practice is an endangered species. More and more, vaccination and treatment decisions are made by corporate bean-counters (accountants) with little or no knowledge of veterinary medicine and a laser focus on profits. My favorite candy bar is now made by the same folks that own Banfield and VCA Pet Hospitals, Mars Inc. When their candy bar profits are not sufficient, my Mars Bars get smaller. When veterinary revenues are not sufficient, I believe that more reasons are found to bring your pet to their corporate veterinary practices. Banfielding is no less common at the other multi-locational veterinary hospital chains that crowd out independent animal hospitals throughout America – and not limited to intensive marketing of their vaccines. See here:

Patronize your local independent veterinarians – the animal hospitals with 1-3 staff veterinarians and a single location. When that establishment sends you your yearly or periodic vaccination reminder, thank them and tell them that you do not feel your pet needs shots, but that you would like a thorough veterinary health exam of your pet just the same. When you find a veterinary service at a lower price in some discount location or non-profit spay-neuter clinic, think about the economic ramifications on your traditional small animal veterinarian when you go there. If independent, caring veterinary hospitals are all consumed by huge profit-driven corporations, it will be the fault of the public for not realizing that monopolies never function in the public interest.

Science-based veterinary medicine does not exist in a vacuum. Young veterinarians today graduate with substantial student debt. Many of the sources of revenue that veterinarians relied upon in the past for their livelihood have vanished. You order your veterinary prescriptions online from Chewy. Tight family budgets and time constraints limit the number of veterinary visits you make. You look for convenient, big-box, gas-&-go locations open 24/7. The vets at those 1-3 staffed facilities went to school for 6+ years to learn how to prevent, diagnose and cure disease – they should not have to stick dogs and cats unnecessarily in assembly line fashion. If you do not utilize their healing expertise, day-by-day, year by year, there will be less of those independent veterinary hospitals to visit. You will be left with amoral, loveless, megacorporate practices run by bean counters, and you will be to blame for that – no one else.